📕 All the Way to the Memoir, Part One

A non-take on Elizabeth Gilbert's new book and surrounding Discourse™

“One day, I had a horrible idea and I shared it with my wife. I told her I was thinking of writing a collection of personal essays, and if I did it would take me years to write it, and even if I sold it, I’d barely make any money.

She said, ‘Oh my God. You have to!’”

—, author of A Paper Orchestra, in ’s Questionnaire #136

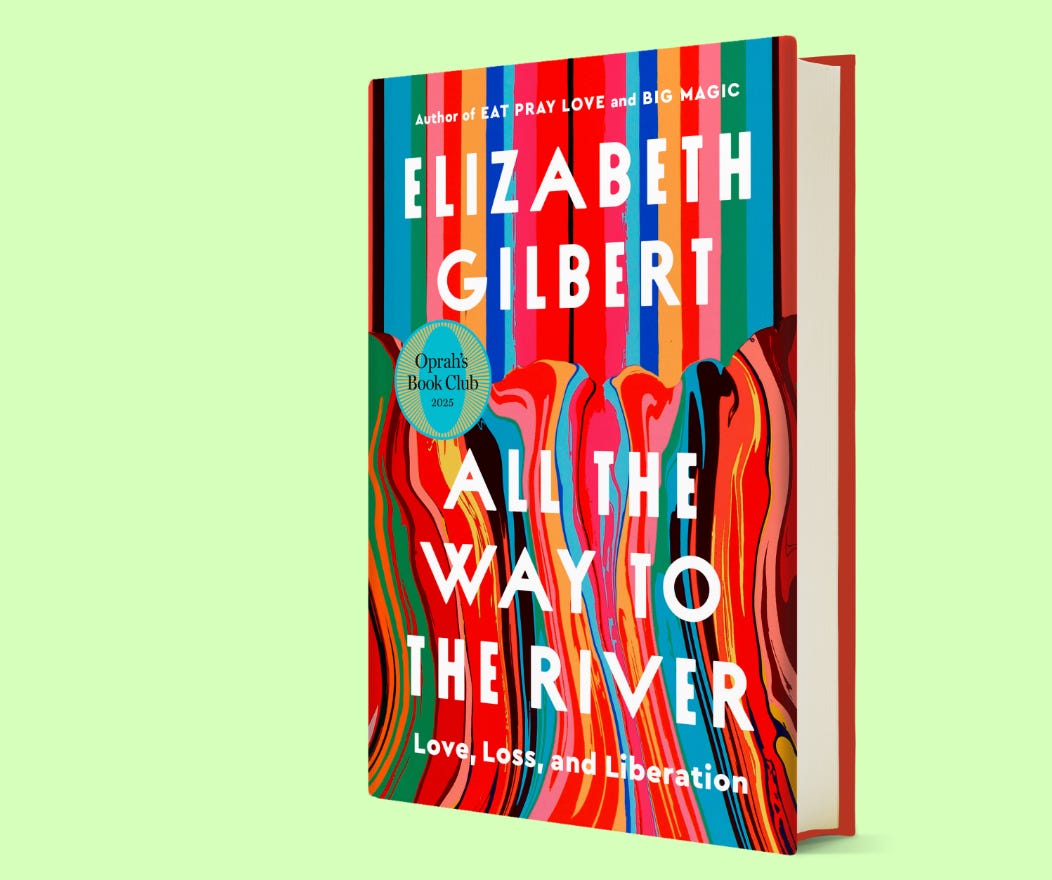

Forensic. That’s the one word bestselling author and Oprah-bestie Elizabeth Gilbert uses to describe her new memoir, All the Way to the River, a story of “love, loss, and liberation,” but really a reckoning with codependency and addiction, infused as much with wisdom from AA (and its related rooms) as her own revelations.

How do I know forensic is her favorite descriptor? Because I’ve spent the last month spelunking down an obsessive rabbit hole, the way a Swiftie might dig through a new album’s lyrics for clues. Clues for what?? I’m writing today’s essay to find out.

Every day for three weeks now, I have searched “Elizabeth Gilbert” in Spotify podcasts (or Apple if that’s your thing), refreshing to see if a new interview dropped. And drop they did! Rich Roll, Monica Lewinsky, Oprah (replete with Starbucks SponCon 🙄), and at least a dozen more.

I jumped to listen (more clues!), no matter how many times I’ve heard the same stories, told the same way. I don’t care. I must be looking for something.

No one ever accused me of a “hot take.” Consider this a tepid take, one month late.1

If I wanted to jump on the trend-jacking bandwagon, I would’ve written some sort of smartie takedown after the excerpt in New York Magazine’s The Cut went live at the end of August, similar to the hordes that excoriated LG in the comments, a mob of word-sword-wielding critics, even without having read the book yet.2

Liz is no book marketing dummy; the excerpts are designed to spark precisely these types of pearl-clutching reactions. She knew she was highlighting the aspects of her worst self, serving up her gnarliest confessions to us on a silver Discourse™ platter. Delulu is the Solulu, after all.

The “nice Eat Pray Love Lady” (her words) threw some self-flagellating chum in the water—self-identifying as “a skid row sex and love addict and a blackout codependent”—and it worked:

“I can’t even tell you when I collapsed into the utter abandonment of self that is codependency in its most deadly and life-destroying form. I can’t name the exact moment when I made her into my higher power, or when I surrendered all my will and agency to her, or when I decided that it was my job in life to serve her every desire — no matter how much it cost me, physically, emotionally, or financially.”

Before reading the full excerpt and screen-shotting the comments with abandon (cautions-to-self to avoid the same fate?), I read Jia Tolentino’s essay in The New Yorker, “Elizabeth Gilbert’s Latest Epiphanies,” also two weeks before the book’s release on Tuesday, September 9.3 (In 2017, Jia declared, “The Personal Essay Boom is Over,” but still went on to publish her brilliant book of essays, Trick Mirror, two years later).

Jia’s review—zooming out on Liz’s broader career, not only the latest book—broke my brain a little bit, as she called attention to the cycle of revelation, rehab, repeat (emphasis mine):

“Gilbert’s most pervasive influence can be found online, in the breathless having-just-finally-realized tone that dizzying numbers of women who narrate their lives on the internet have adopted. On social media, many of the most chaotic and emotionally lawless people you’ve ever known are posting on a regular basis about having at long last achieved inner peace. Many among us, after observing this cringe-inducing side effect of regular self-narration at mass scale, have given up altogether on sincere ideas of personal epiphany.

But even those who might seek to subvert that tone, or invoke it ironically, are negotiating the same conventions. Gilbert may be patient zero for the latter-day memoirist mind-set: so many women—and I would never exclude myself—have come to believe, at some level, that they, too, are Elizabeth Gilberts, people who search hard and love harder, whose personal journeys can and should captivate millions, whose flaws and failings only make them better heroines in the end.”

Is that me? Am I, too, an aspiring Elizabeth Gilbert™? I did follow in her footsteps on a self-searching sojourn to Bali five years after reading EPL. Jia made sure to toss the most salacious judgment-inducing jewel from Liz’s new book into her piece—the premeditated murder confession—served with a side of snark (emphasis mine):

“In time, Gilbert becomes a twisted bedside nurse, tying off the arms of a ‘venomous junkie’ who has already lived nine months longer than the doctors thought she would. And yet this off-kilter enabler remains Elizabeth Gilbert, a woman who could, in under thirty seconds, locate transcendent human insight in a nuclear-waste dump. She tells herself, ‘Rayya is my most beautiful story.’ Then, losing the faith, she decides to murder Rayya, literally, by switching her morphine pills with sleeping pills and covering her in fentanyl patches—a plot that fails only because Rayya somewhat demonically cottons on to the plan and thwarts it.”

Jia knows what Liz knows: this part of the story is designed to incite your rage, your shock, your horror, and your judgment—and yet, it is still Liz’s capital-T truth. She prioritizes strong and true storytelling even above what you think of her. And she will judge herself before you can, spelling it out slowly and directly in the book (and this Guardian excerpt), so you don’t have to wonder if things really got this bad or not, if she was really this deranged or not (emphasis mine):

“I decided I would do it the next day. I went back to sleep that night in peace, knowing that liberation was finally in sight. I want to make something extremely clear here: when I say that I once planned to murder Rayya, I don’t mean that the idea simply crossed my mind that my life would be easier if she were gone. I mean that I fully intended to kill her. And I tell this story in all its raw honesty, because I want people to understand how insane codependency can make a person become. I mean, I’m the nice lady who wrote Eat Pray Love. And I came very close to premeditatedly and cold-bloodedly murdering my partner because she had taken her affection away from me, and because I was extremely tired.”

Who is telling us this story? It isn’t the sleep-deprived Liz Gilbert of then; it’s the six-years-sober Liz of now, the author. But even now is a misnomer; a book takes years to write and edit, and once it is released into the world, it too becomes a fossilized record of the author’s older self. We don’t know what’s next for Elizabeth Gilbert, and we shouldn’t need to. That’s not what memoir is for.

Now, will we still take any present-day revelations with a larger grain of salt, having noticed the gap between her social media presence and what was actually happening behind the scenes for the last decade? Also yes. And that’s healthy; no one can sustain a perfection pedestal, and certainly not at those unfathomable levels of fame.4

I had the privilege of listening to a live conversation with writer and podcast host and yesterday; in it, Sherry outlined the three voices within memoir or personal essay: the storyteller, the reflector, and the universal:

The storyteller narrates in the moment (I sat on a bench and plotted her murder)

The reflector derives meaning from the events (in Liz G’s case, seven years later)

The universal voice weaves these insights into a broader conversation we can all be part of (Liz isn’t the only one struggling with codependency and addiction; the book is a “forensic exploration of how two people with the very best intentions end up bringing out the very worst in each other.” ).

This is similar to how describes a good memoir, one that incorporates the me, the we, and the The. I also appreciated ’s book, Deep Memoir, for more on this.

In addition to mainstream press coverage, naturally several articles went viral on Substack, too. One of my favorite “takes” isn’t a take-down at all, it’s co-founder ’s fair-minded essay (and related podcast episode), “Memoir is a Mirror.” In it, she writes:

“Dear readers, newsflash. Memoir is self-indulgent in the same way taking care of yourself is selfish. If you don’t like reading books about people’s personal lives, and how they makes sense of their experience, memoir is not your genre.”

BOOM. Perhaps that’s the clue I was looking for . . . a permission slip, one that reminds me not all feedback (on my writing, my personality, or my failings) is created equal. I restacked Brooke’s PSA with my own note:

“I started blogging twenty years ago . . . early on, someone close to me called one of my most vulnerable posts navel-gazing in a two-page reply. It’s been a nagging voice on my shoulder ever since, so I am going to call forth this line while writing here on Doh, an ongoing effort to muster the courage to share what I know might help others feel less alone.

If you are uncomfortable with personal essays, there’s no need to read mine! And I can free myself from pleasing someone who doesn’t agree with the genre in the first place, let alone any specifics I am called to share. We’re all better off that way.”

The clues continued accumulating. While recording for her podcast yesterday, my friend asked if I was working on a fourth book. I recalled ’s words, quoted in the opening epigraph at the top of this post. It’s a terrible idea, at least business back-end-wise, and yet I’m not sure I can avoid it.

My husband Michael, a contemporary artist, is as supportive as Michael Jamin’s wife, regardless of the capital-producing outcomes (or not). After Jamin quotes her saying, “Oh my God. You have to!” he adds, “She thought it would help me find myself, and she was right.”

Rolling in Doh is my antidote to the self-help revelation problem: this space allows me to breathe, because I have relinquished my role as The Expert. Thank you, Great Humbling, of these last five years, for releasing me from the naive idea that I know anything at all, other than what it feels like to live a prolonged Flop Era. As Saul Bellow said, “I am not an ornithologist — I am a bird.”

I also appreciate Slip author ’s addition to the genre, telling fellow authors, “You are a Memoirist, Not a Therapist.” In her new book, Mallary is deliberately shining light on the messy middle—and lo, even publishing her story as such!—rather than presenting a perfect resolution/conclusion, one that so often becomes a false front, given that we are all flawed and perpetually figuring things out.

In contrast to Jia’s lens, Elizabeth Gilbert told Modern Love podcast host Anna Martin that she didn’t write this book to help people, per se. Her primary goal was telling the best possible story while honoring Rayya’s life in the process, and if it helps or—in proper self-help parlance—serves readers, well, that’s a bonus.

She asked her publicity team not to share reviews with her, good or bad, so maybe Liz has no clue about the swirl of conversations surrounding the launch. The best quote from the publicity bonanza, the one that leaves me more agape than the murder-plotting, is what Elizabeth Gilbert said to in an interview for New York Magazine:

Did you worry about how the book will be received?

No.

No?

I don’t think that was why it took so long to write. Truly. I truly think that I didn’t know what had happened and I only knew how it felt.

. . . And now that it’s done and I feel really grounded in the expression of this book, I feel really settled. That’s what I was trying to say. That’s why all this went down. This is what it felt like. This is what it means, who she was. This is who I am. I feel really relaxed actually about putting it out into the world. In a way, my part of the job is over. I have the public-facing part of the job now, which to me is much simpler than the writing of the book. The public-facing part is just like, I’ll go to the places and I’ll answer the people’s questions, and they’re a lot easier to answer now because I feel like I do understand what occurred.

Emily—herself a reigning queen of viral very-personal essays—replies, “Wow, I’m so jealous.”

Me too.

Given how critically the book has been received, I would be balled in a corner sobbing hysterically by now if I were in Liz Gilbert’s shoes, and hadn’t yet thickened my skin by fending off years of these verbal slings and arrows. Unless I was laughing all the way to the bank? Doubtful . . . imagining this kind of character attack feels like it would kill me, no matter the financial reward (and let’s be real, that’s only for the top 0.01% of authors anyway.)

I’m not here to judge Liz Gilbert’s life choices, though it pains me to admit that was an early reflexive reaction, or even to judge her book and tell you exactly what I think about it; I’ll leave that to the professionals.5

Perhaps all my rabbit hole “research” surrounding this launch has been guided by the fearful writer in me, aspiring to absorb even a fraction of the courage these women—and every memoirist, for that matter—generously offer through warts-and-all Truth sharing in spite of what any of us thinks about it.6

I can only hope to do the same someday.7

❤️

Continue reading part two on the schadenfreudic release around water cooler conversations:

😢 No surprise, diving into all this Discourse™ and the podcast circuit too early spoiled my experience of reading the actual book. I wish I had the patience to wait!

😡 Sadly, much of this evisceration is gendered, biased against women and the many impossible standards society insists they adhere to. As one astute NYT commenter pointed out in response to Elisabeth Egan’s “Excruciating Missed Opportunity” review of the book, readers celebrated Charlie Sheen for his honesty at the same time as raking Elizabeth Gilbert over the coals for hers:

“I read the other NY Times article about her new book a couple days ago, and now this article. In the interim I read the article about Charlie Sheen’s memoir, also on this site. I can’t help but notice that the comments about Gilbert’s memoir are overwhelmingly negative (she’s a narcissist, etc) while the comments about Sheen’s memoir are overwhelmingly positive (addiction is a terrible disease, glad to hear he’s doing better now). The contrast is glaring. Hmmm…I wonder why that could be?”

😬 The penultimate paragraphs of Jia’s essay also singed a shame-prone soft spot of mine, as I consider how I would write a next book without doing exactly this, pulled like a magnet by a market and publishing industry that rewards shiny self-helpy take-aways tied in a bow:

Five years later, she published an essay in the Times Magazine called “Confessions of a Seduction Addict,” which ends with her choosing to walk away from an encounter with a love interest in a park. “And that’s when I realized that the better part of my life had already begun,” she writes.

And there it is again: the new revelation, the better life arriving once more. If you’ve read any celebrity profiles about youngish female stars during the past decade or so, you may have noticed that each woman, no matter what, is always stepping into her truth and power—she will also be stepping into her truth and power three years from now, when she promotes her next thing, and she will certainly be stepping into her truth and power five years after that. Every time, the person you’re seeing will really, finally be her. This, too, may reflect Gilbert’s influence on the culture. But the problem with this amnesiac perpetual becoming is more about the medium than the project. Within our real lives, we do have to always become ourselves. We do have to hope, at periodic intervals, that we’ve actually figured something out. We have to both consider what we’ve learned and also, humiliatingly, continue learning. It’s only when we are confronted with our own record-keeping—in a journal, a post, a memoir—that we see the shelf life of whatever we considered our truth and/or power before.”

🪙 With my 0.5 cents I will say: I also don’t care for the poems (the drawings are fine), and it’s very heavy on twelve-step language and framework—which might be a good thing to expose those of us who are less familiar?

The podcast tour strikes me as a subtle form of novelty-seeking similar to the addictions she describes struggling with, as there’s dopamine in self-disclosure, too. I know, because it’s hard not to love the high when I do the same here on Doh.

🤔 I’m well aware that LG has far less to lose financially than me. If I were to spill my guts in a book and have the effort flop, or actively impede future client work, I don’t have millions in royalties to fall back on. Will that stop me if I still hear the soul instruction to write on? Probably not.

👉 If you enjoyed this post, you might also appreciate:

Excellent post!

Loved all of this, and especially this: “But even now is a misnomer; a book takes years to write and edit, and once it is released into the world, it too becomes a fossilized record of the author’s older self.”

I am having visions of Lizzy G sitting in her church, blissfully unaware of any of the negative press or reviews. Of someone asking her “have you seen what they’re saying?” And her answering (truthfully) “no idea.”

“I’m writing today’s essay to find out.”

Dear Jenny, you detective, seeking clues, tying threads together to weave a net to catch the truth. It’s a never ending endeavor, of course.

I have been quiet recently, mourning Iryna and Charlie and all that has been stolen from us by fear, hate and brokenness.

Even so, we get to go on.

Elise Devlin wrote about how British Commonwealth champion boxer Stacey Copeland handled fear in NYT’s The Athletic’s Peak series a few days ago. The UK didn’t lift its ban on women’s boxing until 1996. Stacey was afraid of her opponent and none of her previous mental strategies for dealing with fear were working. Then she remembered about how when she was 11 and not allowed to box, she would have given anything to be in the position she was now in.

You were born to write, Jenny, don’t let anyone or anything make you question your true self.