🙃 Are You in Your Flop Era?

Welcome to the club, if so 🙌

“It seems like people aren’t as into in-person events anymore,” he said. “They’re over it. Registration has been so thin the last few years.”

“Hmm, I’ve experienced the opposite,” I countered.1 “People seem even more grateful to be together when they can be at conferences and meet-ups. I’m more inclined to think it’s just that they can’t afford the expensive registration and travel fees right now—or even if they could, they are being more conservative about spending that money.”

He looked at me like I had three heads. My words did not square with his experience. “But the media says the economy is great,” he replied. “All indicators are up.” My turn to look aghast.

I admitted I may have a selection bias of sources. Given how open I am here on Doh, friends going through a rough patch likely seek me out to discuss business challenges. But nearly all the small business owners I have spoken with this year, in private calls behind the scenes, tell me it is their hardest year in business—by far. It has been quieter than 2020, for sure, and surprisingly harder to land B2B work.

Many are seeing and hearing crickets where their client pipeline used to be. We are carrying debt, dipping into savings, and unsure when the financial bleeding will end. Is it us? Is it something we are doing or not doing? Or are we all getting pulled under by the riptide of late capitalism?2

I gave a few personal examples: There’s no way I could shell out $15K for TED again after two years of attending. I’d have a hard time justifying even a thousand-dollar conference ticket to my Inner CFO right now. Even J-Lo canceled her tour amidst personal turmoil and flagging ticket sales.3

This man must not be in his Flop Era, I thought. What is that like?!

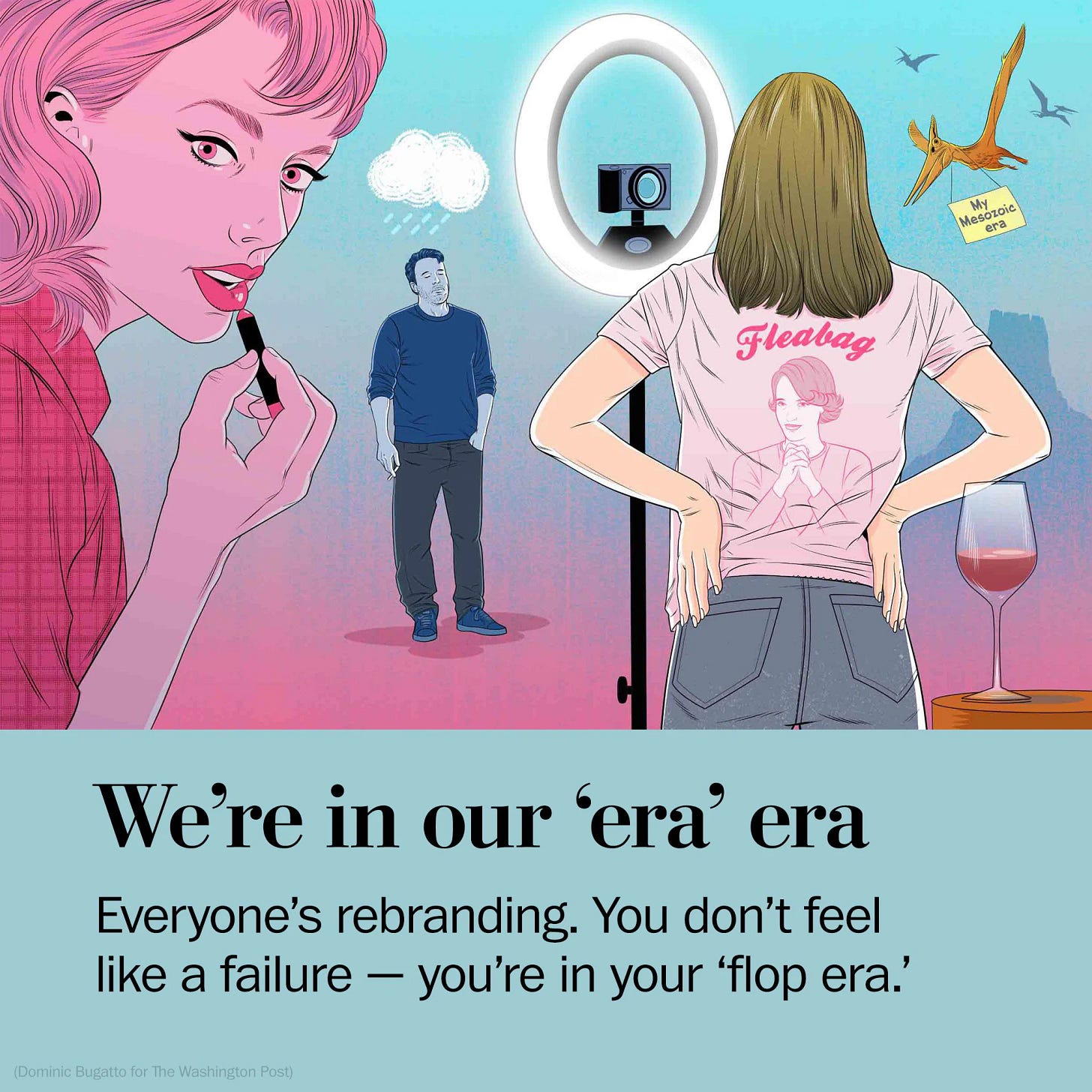

Declaring a personal Flop Era is not a new phenomenon, but it did reach new heights in the pandemic. Twitter enjoyed a surge in the 2010s, and TikTokers ran with it in 2020 and beyond. Know Your Meme defines it as follows:

Flop Era or In My Flop Era describes a period of time when an artist, typically a musician, is only producing flops. It is also used more widely to describe organizations and individuals as going through a tough time or period of disappointment. It is commonly used self-deprecatingly and ironically in memes.

My favorite Urban Dictionary definition, from May 2022:

When something goes badly or is unslay.

Person 1: “how was your week?”

Person 2: “i’ve been in my flop era”

Person 1: “ugh that is so unslay”

Along these lines, in August 2022, the Washington Post ran a headline to capture the zeitgeist, “Down and out and extremely online? No problem: Just enter a new ‘era.’” The deck: “Rebound from a breakup with a ‘Reputation era.’ Rebrand your failure as a ‘flop era.’ No calamity is too great or small to be romanticized as an ‘era’ on social media.”

We would be remiss not to mention Taylor Swift’s record-breaking Eras tour, giving Swifties everywhere permission to embrace whatever Era they needed to, finding humor and solidarity with others while dropping the shame of a less-than-fabulous Era. For the Post article, reporter Jessica Goldstein interviewed Rusty Foster, author of the popular Today in Tabs newsletter (emphasis mine):4

Why be burdened with the shame of feeling like a failure when you can just say, hey, it’s only a flop era?

“It’s a way of framing how you feel as a moment that not only allows for change but requires it,” Foster says.

A Flop Era is subjective. My Flop is someone else’s lottery win.

Still, it’s more fun to declare your own, and to own it.

My Flop Era—well-documented here on Doh with over 115 posts and 120,000+ words in this last year—has reconnected me with a love of writing, something I had previously cast aside. Despite the stressors—perhaps because of them—I have been having so much fun with you here reading, experiencing connection with each and every comment, and growing closer with fellow self-employed friends.

“It’s not just you!” we remind each other. “It’s so many of us.”

Is Kevin Costner in his Flop Era? Not according to him! His series of four Horizon films might not succeed by box office standards, but he is following his heart. He is determined not to let money—or fear of losing it—control his creative life. After all, commercial success only reflects a certain type of mainstream taste; as some would say derisively, none at all.5 In an episode of his Self-Publishing School podcast, I remember Chandler Bolt saying they’re called best-selling authors, not best-written.

I walked away from the head-scratching conversation chuckling on the inside, marveling at the gap in our experiences of the last few years.

No one tells you how spiritually freeing a Flop Era can be, despite the heightened fear and sometimes crushing uncertainty. The tension holds possibility and growth. Something new is beginning. Something old is leaving.

What’s to say a Fabulous Era doesn’t bring its own problems? Our minds go on autopilot when we’re happy, as Susan David describes in her 2016 book, Emotional Agility. That means if you’re a creative type, your Flop Era doubles as the perfect compost pile, rich with material to play in.

Slay.6

❤️

Continue reading the next installment in Rolling in Doh’s Flopology™ series:

Economic commentator kyla scanlon coined the term vibecession in 2022, “a disconnect between the economy of a country and the general public’s negative perception of it, which is mostly pessimistic.”

Check out her new book, In This Economy, and her original piece on Substack:

My friend J recommended the book by Neil Howe (who coined the term Millenial), The Fourth Turning is Here, for more on what so many of us are experiencing at the moment. You can find the author in several great podcast conversations here. I was struck by his description of this time as one in which many of us are “shell-shocked by insecurity.” From the book description:

Twenty-five years ago, Neil Howe and the late William Strauss dazzled the world with a provocative new theory of American history. Looking back at the last 500 years, they’d uncovered a distinct pattern: modern history moves in cycles, each one lasting roughly eighty to one hundred years, the length of a long human life, with each cycle composed of four eras—or “turnings”—that always arrive in the same order and each last about twenty years. The last of these eras—the fourth turning—was always the most perilous, a period of civic upheaval and national mobilization as traumatic and transformative as the New Deal and World War II, the Civil War, or the American Revolution.

As reporter Yarimar Bonilla writes in her op ed, “I can’t revel in J.Lo’s fall from grace,” I also take no pleasure in the tour cancellation or possible Bennifer break-up (unless, of course, those moves are what’s in the highest good for all involved). Bonilla speculates on why J.Lo’s recent mille-feuille flurry of releases haven’t resonated:

“For someone who’s reached the pinnacle of fame and wealth but struggled romantically, this might be meaningful. But for the rest of us — amid wars, post-pandemic inequalities, inflation, civil rights erosion and a terrifying election — a multimillionaire’s personal quest to find love just doesn’t inspire.

. . . “This Is Me … Now” has quickly faded into pop culture history. And the love story that inspired it is now rumored to be unraveling. If true, perhaps this will be the catalyst she needs to finally break free from fairy tales and clichés and step into her power once again.”

I’m a big fan—The New York Times did a great feature on Rusty in April: From a Tiny Island in Maine, He Serves Up Fresh Media Gossip. “Rusty Foster could never live in New York. But his hit newsletter, Today in Tabs, is an enduring obsession of the city’s media class.” Rusty then shared his experience of the process behind the paywall in Spilling the T.

See also: this so honest-it’s-cringe interview titled “When Ruthless Cultural Elitism Is Exactly the Job” with literary agent Andrew Wylie. He told reporter David Marchese that,

“How do you understand the contradiction that the crappy books that sell so well are what allows for the publishers to pay big advances to your writers? You need the crappy stuff to do well, right? That is the publishers’ view.

What’s your view? Different.

Explain the difference. One, the goal of the people we represent is not to be Beyoncé. It’s not directly connected to popularity. Let’s say you’re inviting some people to your house for dinner. Do you want everyone to arrive? Or do you want a select number of intelligent people who are amusing and understand what you’re talking about? The latter, I think. There are some people I don’t want to have join the dinner. They deserve to live, but they don’t need to come to my house for supper.”

And later in the conversation:

I’ll ask in a different way: Has the status of serious writers changed in the country? I think that’s the wrong way to look at it.

What’s the right way? What are your goals?

To matter in the culture? No. Absolutely not. Who gives a [expletive]? You want to matter in this culture? Not me.

So what should a writer’s goals be? Just on the quality of the work. The kind of ineffable beauty of something extremely well expressed.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also appreciate:

💬 How do you collect stories and ideas? 🐿️

“I am a compost heap, and everything I interact with, every experience I’ve had, gets shoveled onto the heap where it eventually mulches down, is digested and excreted by worms, and rots. It’s from that rich, dark humus, the combination of what you encountered, what you know and what you’ve forgotten, that ideas start to grow.”

I’m wondering in a self defining’Flop Era’ is in fact another way to turn this into a win, meaning not really sinking our teeth into what’s not working or taking a minute to consider what we really want.

Greetings from my flop era