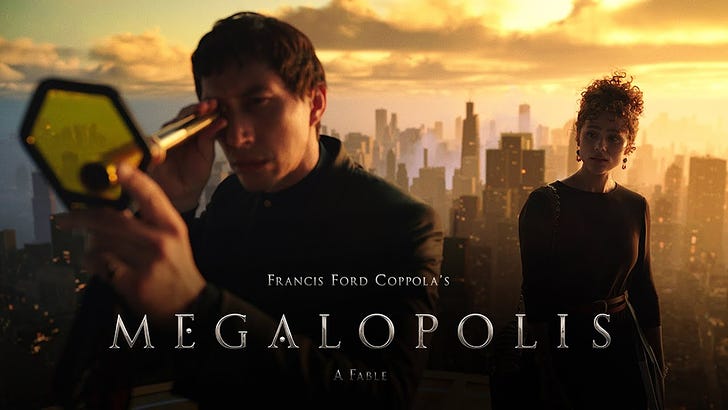

🎬 Megaflopolis, Part Two: "You can't be an artist and be safe"

“It’s so silly in life to not pursue the highest possible thing you can imagine, even if you run the risk of losing it all. Because if you don’t pursue it, you’ve lost it anyway.

You can’t be an artist and be safe.”

—Francis Ford Coppola on Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso

Catch up on part one first:

I wasn’t expecting to write a second post on Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis boxoffilice flop, except that the morning after part one went live, I coincidentally heard Coppola on one of my favorite podcasts, Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso.

Fragoso is a genius of the format—unmatched in the depth of his research, the richness and intimacy of his conversations with A-list luminaries, and remarkable how he draws upon such a vast cultural map to make connections with and for his guests. He does this while shaping a strong narrative arc within each episode, even though, from the outside, it appears to be just another interview podcast. He’s an enigma—erudite, warm, and sharp—and only thirty years old.1

Meanwhile, Coppola is 85 years old and sold part of his winery to pour $120 million into a movie that has so far yielded only $9.5 million in worldwide ticket sales.

So when I saw his interview go live a day after my last Doh post, I felt a little deflated. Oh no! I am missing a critical piece of the Coppola puzzle! I knew Fragoso would ask all the unanswered questions I still wanted to know, and he did.

I wanted to know how Coppola felt about risk and failure, what it meant to him, how he weathered storms like this latest typhoon of abysmal results and press for a project he dedicated his heart (and money) to over a span of forty years.

Not once did he say he measured success by box office results or statuettes. After winning five Oscars for The Godfather, he threw them out the window in rage, shattering them to pieces, after Paramount turned him down for funding Apocalypse Now. “What good are these?!” he said, if, after a record-breaking streak of wins he still couldn’t secure studio investment for the following project.

Coppola’s most meaningful metric isn’t money. It’s taking his shot, and hoping to inspire mentors, peers, and young people along the way.2

Looking back on his career, he said, “I have had what is, to me, the greatest reward of all—when a filmmaker that I admire comes to me and said, he became a filmmaker because he saw Apocalypse Now or Rumblefish.”

It’s not like Coppola has unfailing confidence. Growing up as a younger brother yielded constant comparisons with his older, more handsome, more successful (for a time) prototype. It colors how he sees himself compared to contemporaries, even now.

“I’m not like Scorsese or Spielberg or Lucas,” he told Fragoso. “They were born to do this. I think I have genius but no talent, really.”

See?! Coppola doesn’t need basic betches like me to tell him he lacks talent! That his new film is a flop! Oddly, he already knows that about himself—that might be lacking something in the talent department—and I often feel the same way, at least about the talent part. There’s a cavernous gap between my reading taste and my writing skill. It’s refreshing to hear even Coppola say it out loud, and to keep producing work anyway.

One of my favorite Cheryl Strayed nuggets is “surrender to your mediocrity.” For her, this life-changing insight allowed her to finish her first novel after ten years of false starts, insecurities, and not taking it seriously enough.

“Surrender to your mediocrity is one of my essential writing tips,” she said. “Get out of your own way. You’re not sitting down as the talented writer, you are just sitting down as yourself and doing the best that you can.”

One of the biggest consequences of a flop—a real-life one, not just the confidence blow—is potential financial wipe-out, a risk outcome my dad calls “all in, fall flat.”

This can then can result in a second- or third-order failure to secure future funding from the gatekeepers who only ever want to see number go up. Publishers won’t buy an author’s next book if the previous one doesn’t sell, which puts a sense of career make-or-break pressure on authors to never let the numbers slag, no matter what world events interfere with the launch.

When Fragoso asks Coppola if “this movie [and the utopia it depicts] is the place he still longs to live in,” Coppola replies, “Well, I know I’m done with Megalopolis because I am just finished a new script of something I want to begin.”

While we’re here mitgefühlserleichterungsfreudeing over his failure,3 he has (at least somewhat) inoculated himself by already moving on. Coppola isn’t letting the sales results destroy him. His love is in the craft, and always has been. That said, he is still hoping for studio funding for his next film.

“I have the script and I’m hoping I can find financing for it,” he said, “because I can’t just keep borrowing money to make movies.”

In the very last lines of the Talk Easy conversation, he served a cliché:

“You know what the secret of it is? Of life?

What tickled me was the part he didn’t say:

. . . and the money will follow.4

❤️

I love the Talk Easy show (and logo) so much that I even bought one of his mugs. For more on his process, check out this FT Weekend conversation:

My friend Jay Acunzo coined this term, Even More Meaningful Metrics, in our Free Time conversation. For example:

Unsolicited Response Rate (URR): When he publishes something and someone feels urged to respond in some way without being prompted. (Jay)

Cackles Per Piece (CPP): moments during the process of creating that cause so much joy he cackles out loud. (Jay)

OWBR: Open to write-back rate (Ann Handley)

NNFM: Number of New Friends Made from podcast interviews (JB)

Guest Gratitude (GG): During an interview, “No one has ever asked me that before” or “that was fun” afterward (JB)

WOM Shares: People who write in and say they’ve already shared/bought the book for friends or team members (JB)

From the Kevin Costner post, mitgefühlserleichterungsfreude is my made-up word for empathy-failure-joy, or feeling empathy and even a little relief when hearing about someone else’s failure; not wishing any ill-will upon them, but grateful to know you’re not alone in a Flop Era.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also appreciate:

Happy birthday, Jenny! Thank you for doing what you love and sharing it with us.

Beautiful, Jenny. So few of us ever master the skill of detaching from the outcome and doing the work because we love the work. It's also fascinating to me that the more money we have, (maybe) the more money we throw at the "problem." It feels like Costner and Coppola both fell victim to this. There's something about constraint that can fuel creativity, though I don't blame them for trying to realize ambitious visions. Courageous artists probably wouldn't be satisfied with less.