🦌 Fawning and the Fifth F: FLOP (Part 4)

Flopology: a prolonged failure to pivot, and why that might be a good thing

Catch up on part one, part two, and part three first:

“Last night as I was sleeping,

I dreamt—marvelous error!—

that I had a beehive

here inside my heart.

And the golden bees

were making white combs

and sweet honey

from my old failures.”

—Antonio Machado, excerpted from “Last Night As I Was Sleeping”

Back in 2008, when I trained for running my first-and-only marathon,1 everyone warned me about mile twenty. That’s when one might bonk or “hit the wall,” experiencing sudden fatigue after depleting the body’s glycogen stores.

It’s when newbies most want to quit, feeling utterly gassed mentally and physically, no matter how long the training runs were leading up to the big event. Something about the excitement of race day makes it easy to go overboard at the start, bonking by the final third when you realize there’s still six to ten miserable miles remaining, and your whole body aches after the first eighteen.

If you can push through it, no matter how fatigued, an energy surge tends to kick back in around mile twenty-five or twenty-six, when you can literally see the finish line ahead—along with the cheering crowds, those shiny human-sized foil burrito wraps wrapped around victorious finishers cooling down, and in the case of the one I ran, hot shirtless men holding silver trays piled with iconic teal Tiffany boxes (not joking) containing a commemorative necklace for the occasion.

If only life and business changes were so clear-cut—and so neatly rewarded.

So far, we’ve been exploring the body’s wisdom and automatic survival mechanisms when under threat:

Physiologist Walter Bradford Cannon first put labels to these automatic mechanisms, coining fight-or-flight in 1914.

Researchers added freeze late in the twentieth century, though of course many animals have had a freeze response to stay safe for as they’ve existed.

In 2003, psychotherapist Pete Walker coined the idea of a chronic fawn response as it relates to codependency and cPTSD (picked up beautifully by in her book, Fawning, the inspiration for this series).

In the years since, some have added faint as a fifth F (i.e. passing out at the sight of a needle or when in immediate danger), and/or the one that grabbed my attention: flop.

For Doh purposes, we will not look at this through the lens of acute trauma—horrible attacks, abuses, and/or life-or-death situations where surviving at all is heroic. Instead, we’ll examine the impact of low-grade ongoing stress, particularly in the entrepreneurial arena, that might induce a chronic, adaptive flop response, just as we’ve been exploring with fawning.

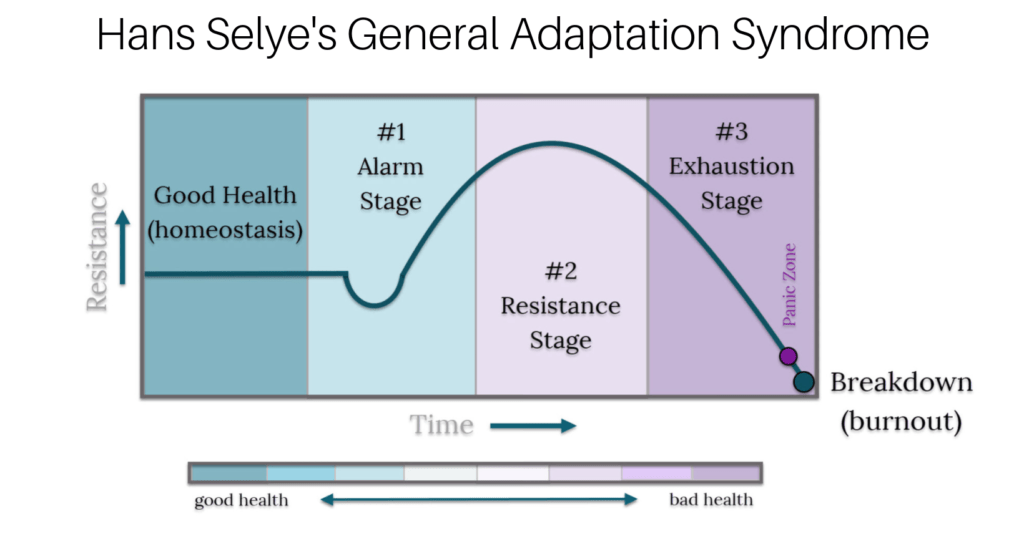

We can also reference research from endocrinologist Hans Selye, who introduced the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) theory for understanding how the body progresses through three stages when under ongoing stress:

Alarm: This initial stage is the body’s immediate response to a stressor, triggering the “fight-or-flight” response.

Resistance: If the stressor persists, the body enters this stage, attempting to adapt and maintain homeostasis, potentially leading to fatigue, irritability, and difficulty concentrating.

Exhaustion: If the stressor is prolonged and unresolved, the body enters the exhaustion stage, where resources are depleted, leading to increased susceptibility to illness and potential health problems.

For many entrepreneurs, myself included, the start of the pandemic motivated us to double-down—to fight—for our businesses, our safety, our health, our families, and our income (aka survival of basic needs on Maslow’s hierarchy).

But once our surge capacity was depleted, whether one month or one year or two years in, some of our bodies shut down from the chronic stress and uncertainty of it all. I know mine did.

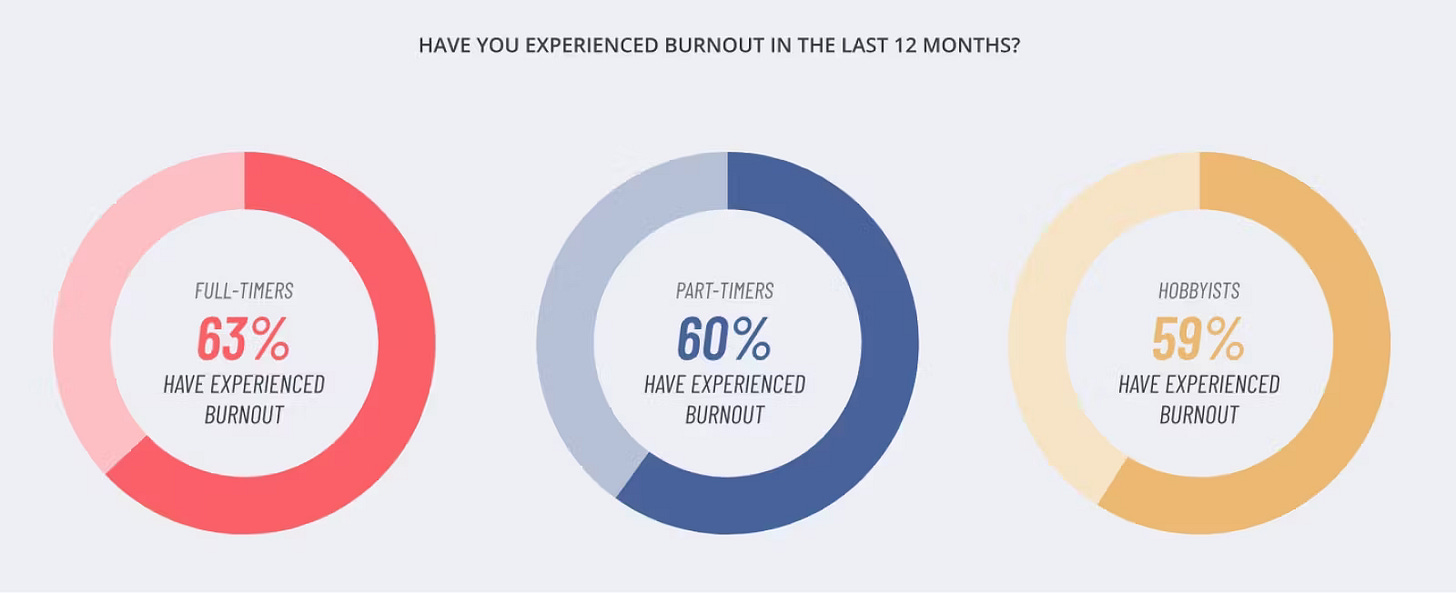

Creator burnout is a well-known never-ending treadmill, as people who make a precarious living online struggle to keep up with the hungry ghosts of insatiable Big Social Algorithms.2 Kit’s State of the Creator Economy report shows that 63 percent of full-time creators have experienced creative burnout in the past year:

In her 2018 book, Squeezed, Alissa Quart coined a term for this entire wobbly-and-confused cohort: the middle precariat, or “people who thought their education or background would mean they would end up comfortably middle class but have, instead, found themselves squeezed by financial insecurity.”

Like , one of my favorite authors and thinkers, I, too, somehow find myself on the unsustainable hobby side of a once robust(er) career.3 While each of us must take full responsibility for our lives, we are also doing so while responding to economic forces, systemic rot, and platform pressures largely outside of our control.

In another post, “How to Surrender Without Giving Up,” Sara quotes (follow me here!) Producer DJ Cashmere, the interviewer for an episode of 10% Happier, paraphrasing remarks from former Buddhist nun Kaira Jewel Lingo:4

“There are moments in our lives where giving up really is the best we can do. Circumstances are so overwhelming that our best bet is to just shut down. Our best bet is to just walk away, and we might just need to be done with something at least for the time being.”

Sara summarizes it thusly: “Giving up means pulling down the shades and getting under the covers. Surrendering means accepting the situation as it is and working from there,” and when needed, you can even “surrender to the fact that you can’t surrender right now.”

As the resident flopologist here at Rolling in Doh, my working definition for a Flop Era, at least in the context of business/career, is a prolonged failure to pivot.5 It’s when you’ve tried a little bit of everything, and nothing seems to be working at the scale that would catapult you out of the muck and into the wind-blown momentum of a new, more sustainable direction. It’s the difference between your phone glitching out on blinking-red low-battery mode and a full charge of time, energy, and money.

Once you reach full blown exhaustion (aka burnout) without a clear way out, that’s when you might want to stop trying altogether, in a form of learned (entrepreneurial) helplessness, or as the always-insightful characterizes it, diminished self-efficacy. A certain despair sets in; nothing I try works anyway, so why keep trying? It might even foment a dark night of the soul. Or a few very dimly lit years . . .

It’s also when you most want to give up. Sometimes it feels like the only remaining option is to surrender—which twelve step programs and spiritual teachers proffer is where new life begins, anyway.

For the times we’re living in, let’s call this the post-pandemic bonk. I don’t have to tell any of you long-time Dohnuts that I know it well. The question is: how and when does a Flop Era end? We’ll grope our way toward ideas together in the next installment (feel free to share yours in the comments).

In the meantime, the main thing is not to quit when you bonk.6

❤️

Continue reading:

🧠 See also: this 2019 research paper on “The ‘online brain:’ how the Internet may be changing our cognition.” I’m afraid to know how much worse it has gotten in the six years since publication!! Emphasis mine:

We explore how unique features of the online world may be influencing: a) attentional capacities, as the constantly evolving stream of online information encourages our divided attention across multiple media sources, at the expense of sustained concentration; b) memory processes, as this vast and ubiquitous source of online information begins to shift the way we retrieve, store, and even value knowledge; and c) social cognition, as the ability for online social settings to resemble and evoke real‐world social processes creates a new interplay between the Internet and our social lives, including our self‐concepts and self‐esteem.

Overall, the available evidence indicates that the Internet can produce both acute and sustained alterations in each of these areas of cognition, which may be reflected in changes in the brain.

👩🏻💻 Sara’s post, “The Amateurization of Everything” ended up being one of her most popular (to-date). Read the follow-up here:

🎧 From 10% Happier with , an episode from November 2024 titled, “An Episode For The Overthinkers and The Stressed”:

📘 In my book, Pivot: The Only Move That Matters Is Your Next One, I define a career pivot as a methodical shift in a new, related direction by doubling down on what is already working. (See full Pivot Glossary here)

🍌 Recall from above that my working definition for a (career or business) Flop Era is a prolonged failure to pivot, living in a limbo-like state that is not generating sufficient opportunities or income. Based on this, follow-up questions for a Flop Era might include:

What do you do when what was working is no longer working?

. . . or when what is working isn’t not financially viable?

Or when what is working is still emerging, not yet clear?

What do you do when the skills or projects you double down on don’t result in renewed momentum?

What is my Flop Era protecting me from? How has it been an intelligent response?

What protections are no longer needed?

In what ways has my Flop Era allowed me to be, do, or create things I might not have otherwise given myself permission for?

From , author of Permission to Rest, What is this transition trying to show me? What wants to emerge here? What am I not seeing?

❌ Here, I refer to not quitting your life, your hope, your support system, and your small, brave steps to turn things around. Let’s call that Big “Q” Quitting.

There is, however, abundant value in Little “q” quitting (although many of these still feel monumental) of outgrown identities, attachments, fizzled projects, toxic relationships, harmful habits, and even entire no-longer-fruitful career paths when necessary.

📕 Perhaps we’ll talk more about this in a future post; in the meantime, I recommend the books Quitting: A Life Strategy by Julia Keller on “the myths of perseverance,” and Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away by .

👉 If you enjoyed this post, you might also appreciate:

"Flop" is a great word, a fun word, a goofy word. Flow and Stop together? That's fine just not at the same time. . .

Jenny, I've been following along closely to this series (and the previous one) because I found myself obsessed with the drama around Liz' new book also. I started checking out times for CODA meetings just in case that was a path I wanted to explore. But as I've recently finished the book on Fawning (coincidentally recommended by Audible the same week you started writing about it), I'm beginning to piece together my own thoughts on these topics.

I love Ingrid Clayton's approach, in that it doesn't blame the person for fawning or people pleasing, but instead locates it appropriately as a trauma response. Maybe this is why I've struggled most with the codependency literature, because it doesn't acknowledge the adaptive function of serving others.

I'm also starting to connect the dots in terms of our political system as well. I've been puzzled why nobody can stand up to an authoritarian leader - maybe collective fawning has become problematic in the Republican party, going along to get along. In light of that, some political stuff makes more sense to me.

I also relate to "performing" in therapy and also doing this when I was getting coached as well. Fascinating that I didn't want the coach to feel they weren't being effective (even if some of them were not) so I always found some way to show they had helped me progress...

Keep doing the brave work! Thanks for sharing along the way. 💗